Criminology is lagging behind

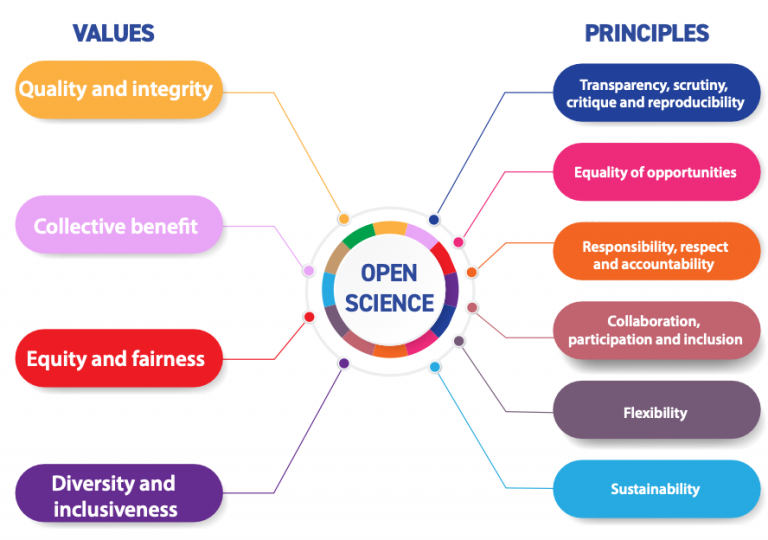

Over the past decade, there has been a major shift in the Social Sciences towards what is often called “Open Science”, which is largely about accessible, transparent, and well-documented research. Indeed, the values and practices promoted by Open Science are closely aligned with the core principles of science itself—principles that seem to have faded under the pressure of the “publish or perish” culture, often at the expense of pause, reflection, and thorough documentation of empirical studies for their later replication or reproduction. To achieve the accumulation of knowledge and advance both theory and public policy, it is essential to generate evidence that is reproducible and replicable – especially in Criminology, where such standards are crucial because this field has direct effects on persons via its own policy. Among the many practices advocated by Open Science, three are particularly relevant in this regard: (1) sharing and/or documenting data, (2) ensuring that analyses are reproducible by sharing code or any other method that allows reproduction, and (3) being explicit about the nature of the study and, in the case of confirmatory research, pre-registering hypotheses. Such research practices enable true reproducibility and replicability of studies, increase the chances of detecting and learning from errors, and, more generally, foster mutual learning within the scientific community. While these are core values of science, they have not always been a systematic part of research practice – but that is now changing.

Psychology has been paving the way in this development. The background is grim: What is now known as “the replication crisis” was the finding that a range of well-known findings in Psychology did not replicate. Indeed, in an empirical replication of 100 studies published in high-ranking journals, only about one-third to one-half of the original findings were replicated (Open Science Collaboration, 2015). Even worse, it seems that this replication crisis affects not only Psychology but the social sciences more broadly, including Criminology (Pridemore et al., 2018).

On how transparency increases scientific rigour

Science is supposed to be self-correcting, but the replication crisis raised serious concerns to what extent that was really the case. There are several reasons for this, but one important part has been a culture of a lack of transparency. This has allowed questionable research practices to go unnoticed or remain uncorrected by the scientific community. Practices such as p-hacking or HARKing (Hypothesizing After the Results are Known) are still accepted by some in the community, or at least by a large proportion of participants in the survey on open science and questionable research practices conducted by Chin et al. (2023). Combined with the difficulty/willingness of publishing null results, which reinforces publication bias, this further increases the risk of inflating false positives.

Beyond affecting the over- or underestimation of effects, the lack of transparency in research can also conceal errors in results that influence political and public debates[1] [2]. A well-known example is the case of Reinhart and Rogoff (2010a, 2010b) and their conclusions on austerity policies during economic crises, which were based on calculations containing errors (Herndon et al., 2014). Similarly, in criminological research, mistakes in code or analytical procedures have led to incorrect conclusions about the effects of public policies. Perhaps one of the most consequential cases is that of Ciacci (2024), who concluded that the prohibition of prostitution led to an increase in rape cases in Sweden. This study has been cited in political debates on the criminalisation of prostitution[3]. It was recently retracted following re-analyses conducted by Adema et al. (2024)[4].

Discovering honest errors is important. Discovering dishonest errors even more so. All fields of research have experienced fraud and manipulation with data (see https://retractionwatch.com/). As criminologists, we should not be surprised that not everyone is always honest, and Criminology is not an exception (Pickett, 2019; Chin et al., 2023). An important part of quality control systems is having the ability to control. In science, documenting data and code, and sharing both, if possible, is the one thing that really makes control possible.

Fields like economics and political science soon followed the culture change in Psychology, and it is now much more common in these fields that journals demand data and code to be shared (Scoggings & Robertson, 2024; Ferguson et al., 2024). The reason is clear: good research is well documented. Whatever we consider the “gold standard” of research cannot be more than bronze, and maybe not even that, if it is not well documented.

Criminology is lagging behind other behavioural sciences – i.e. Psychology, Economics and Political Science – in this regard (Greenspan et al., 2024; Beck, 2025). None of the major criminological journals puts hard demands on sharing data and code. Thus, research published in Criminology journals is not necessarily as reproducible, replicable, and, therefore, as subject to error control as it should be. The reason is that it is often less transparent and well-documented than it could be. At first glance, there seems to be no apparent reason why Criminology should lag behind in this area. While it is true that making documentation openly available entails low effort and cost-effective ways for publishers to make science more open, it does involve an additional effort on the part of authors who choose to make their research Findable, Accessible, Interoperable and Reusable[5]. Of course, there are some pragmatic challenges, as not all data can be openly shared. Some – but not all – qualitative data may have features that makes it more complicated to share, or not at all; this relates specifically in relation to ethnographic data and data from police investigations (Copes and Bucerius 2024). Similar reasons apply to some quantitative data that will not be shareable due to national legislations on data protection (e.g. Nordic administrative data). But all data should be well-documented and, in those cases in which public access is restricted or the data is non-shareable, a statement should be made with information on how it can be obtained or the reason why the data cannot be made publicly available.

For instance, qualitative data is harder to share because complete anonymisation is not always possible. However, some serious considerations have been made to move towards qualitative replication and data sharing tools[6]. Quantitative studies, by contrast, have no reason not to share reproducible code, regardless of whether the data can be made available. Even if not accompanied by the data, analytical code can provide a transparent, step-by-step account of how the data were handled, and what specific analyses were carried out. A similar detailed account of data collection processes and protocols, processing and coding is relevant to provide transparency in qualitative studies.

There are many public repositories in which authors can make their research materials open. Some of these are owned by non-profit organisations, like the Center for Open Science and its Open Science Framework (OSF, https://osf.io/), or for-profit companies like GitHub (https://github.com/) and its public repositories. The authors’ experience in practising open science may change depending on which infrastructure they use, but “free” options to share data and code abound.

On how pre-registration increases scientific rigour

For the sake of transparency and clarity, authors could make explicit what type of research question their study addresses. This not only helps readers to better assess the results but also enables policymakers to evaluate the type and strength of the evidence. In the case of confirmatory research, authors could pre-register their research questions, the hypotheses they intend to test, and the research design they plan to use to test those hypotheses. As Lakens (2019, p. 1) puts it, “preregistration has the goal to allow others to transparently evaluate the capacity of a test to falsify a prediction, or the severity of a test”. In this way, preregistration helps prevent HARKing, ensuring a clearer distinction between confirmatory and exploratory analyses. To encourage this practice, Criminology journals could begin accepting registered reports and adopting in-principle acceptance (IPA) policies[7]. Of course, there is some degree of flexibility when it comes to deviating from pre-registrations, and, as long as such deviations are well justified and properly documented, they should not undermine the validity of the research findings. In the case of non-confirmatory studies, researchers could instead publish pre-analysis plans outlining the study’s objectives and their prior knowledge of the data as a transparency measure, which would limit the researchers’ degrees of freedom for post-hoc analyses.

Pre-registration and registered reports are additional steps that potentially requires more work for both authors and reviewers. Spending additional time might be a hinderance to most researchers. However, most of that is a shift in time in when the work is done. Clarifying the research questions and reasoning for the analytical strategy can be written up ahead of data analyses instead of afterwards. Similarly, reviewers can make qualified judgements on only the research question and design without having to see the results, and quality of writing can be assessed at a later stage.

Actionable Steps Towards Open Science in our Discipline

Now, if open science practices increase the rigour and verifiability of criminological research, should the European Society of Criminology (ESC) promote open science? We think so. Here are three suggestions in which the ESC could play an important role in putting our field up to speed:

- The European Journal of Criminology (EJC; as well as other European criminological journals) should reconsidertheir policy on data availability and reproducibility. Currently, these journals “encourage” sharing of data and code but put no demand. If we are to make a significant impact in the field, our journals should be more ambitious than this. The flagship journal of the American Society of Criminology has stated that they would gradually introduce a new policy to increasingly require open data (Sweeten et al., 2014), and allow registered reports, but since the last board stepped down, the future is once again uncertain. The EJC could consider adopting these practices and serve as a role model for the field.

- Since change must begin at all levels, we recommend that Criminology programs across Europe – at the doctoral, Master’s, and Bachelor’s levels – incorporate a dedicated module on transparency, reproducibility, and replicability, both within academic curricula and in courses designed for these students.

- The ESC awards highlight research that is “outstanding”.[8]. As noted above, for empirical research, lacking data, code[9], and documentation for reproducibility is at best only the bronze standard. Making documentation of research materials (including data when possible) publicly available should be a minimum requirement for anything to be outstanding. Thus, we believe that open science should at least be one of the criteria to be considered for ESC awards[10].

Before concluding, it is worth noting that while we often discuss these practices under the label of “open science”, they are, in essence, about science itself. The call for transparency and openness is not for its own sake, but to live up to standard scientific ideals. It is about research quality and increasing Criminology’s capacity to be self-correcting.

In this respect, the field of Criminology is lagging behind the related fields of Psychology, Economics, and Political Science. It is not because these fields have substantially different challenges than Criminology, but it is a deliberate choice for raising research quality. Raising our standards would strengthen the credibility and impact of criminological research.

Notes:

- Asier Moneva, Alex Trinidad and Isabelle van der Vegt are co-chairs of the European Network for Open Criminology (ENOC)

- The authors are grateful for valuable comments and encouragements from Wim Bernasco, Stijn Ruiter, Amy Nivette, Ferhat Tura, David Bul Gil, and Gian Maria Campedelli

References

Adema, J., Folke, O., & Rickne, J. (2025). Re-Analysis of Ciacci, R. (2024). Banning the purchase of sex increases cases of rape: evidence from Sweden (No. 226). I4R Discussion Paper Series. https://hdl.handle.net/10419/316398

Beck, M. (2025). Mining Transparency: Assessing Open Science Practices in Crime Research Over Time Using Machine Learning [Unpublished master’s thesis]. University of Cologne.

Ciacci, R. (2024). Banning the purchase of sex increases cases of rape: evidence from Sweden. Journal of Population Economics, 37(2), 1-30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-024-00984-2

Chin, J.M., Pickett, J.T., Vazire, S., & Holcombe, A. O. (2023). Questionable Research Practices and Open Science in Quantitative Criminology. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 39(1), 21-51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-021-09525-6

Copes K and Bucerius S. (2024) , Transparency trade-off: the risks of Criminology’s new data sharing policy, The Criminologist 50(2), 6-9, https://asc41.org/wp-content/uploads/ASC-Criminologist-2024-03.pdf

Ferguson, J., Littman, R., Christensen, G., Paluck, EL., Swanson, N., Wang, Z., Miguel, E., Birke, D., Pezzuto, J. (2023) Survey of open science practices and attitudes in the social sciences, Nature Communications,14:5401,https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-41111-1

Greenspan, LG., Baggett, L., Boutwell, BB (2024) Open science practices in criminology and criminal justice journals, Journal of Experimental Criminology, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-024-09640-x

Herndon, T., Ash, M., & Pollin, R. (2014). Does high public debt consistently stifle economic growth? A critique of Reinhart and Rogof. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 38(2), 257-279. https://doi.org/10.1093/cje/bet075

Lakens, D. (2019). The value of preregistration for psychological science: A conceptual analysis. Japanese Psychological Review, 62(3), 221-230. https://doi.org/10.24602/sjpr.62.3_221

Open Science Collaboration. (2015). Estimating the reproducibility of psychological science. Science, 349(6251), aac4716. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aac4716

Pickett, J. (2019). Why I Asked the Editors of Criminology to Retract Johnson, Stewart, Pickett, and Gertz (2011). OSF Preprints. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/9b2k3

Pridemore, W. A., Makel, M. C., & Plucker, J. A. (2018) Replication in Criminology and the Social Sciences. Annual Review of Criminology, 1, 19-38. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-criminol-032317-091849

Reinhart, C. & Rogoff, K. (2010a). ‘Growth in a Time of Debt’, Working Paper no. 15639, National Bureau of Economic Research, http://www.nber.org/papers/w15639

Reinhart, C. & Rogoff, K. (2010b). Growth in a Time of Debt. American Economic Review, 100(2), 573-578. http://www.aeaweb.org/articles.php?doi

Scoggings, B. & Robertson, M. P. (2024). Measuring transparency in the social sciences: political science and international relations. Royal Society Open Science, 11:240313. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.240313 .

Simonsohn, U., Nelson, L. D., & Simmons, J. P. (2014). P-curve: A key to the file-drawer. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 143(2), 534–547. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033242

Sweeten, G., Topalli, V., Loughran, T., Haynie, D., & Tseloni, A. (2024). Data Transparency at Criminology. The Criminologist, 50, 9-11. https://asc41.org/wp-content/uploads/ASC-Criminologist-2024-01.pdf