Criminology of the Damned Questions

Dear Colleagues! Unfortunately, the adverse effects of the COVID-19 pandemic have affected every aspect of our lives, including academia. The first wave of pandemic upended our plans to organize the annual 20th conference in Bucharest as a traditional face-to-face conference. Many other similar events around the world had been postponed for the better days. However, with the assistance of the ESC Board and Secretariat, our Romanian colleagues made it possible to organize the online conference. These efforts turned out to be a resounding success: over 700 participants made it clear that the ESC could effectively react to unexpected challenges and mobilize their members for academic activities despite the critical circumstances.

While the pandemic threat and lockdown policy have a lot of negative consequences and make our life unpredictable, unsafe, vulnerable and upset, in the current situation one can observe at least some positive impact – the compulsory isolation became not only a reliable remedy against the spread of disease but also a proper stimulus for philosophical inquiries and existential reflections. The isolation or alienation can provoke us to "forget" socially objectivised truths, and even start challenging them, asking questions, which in human intellectual tradition has the highest rank of "damned questions". What is the nature of human being, what is good and evil, what is freedom and are we free, what is the life, and why there is so much injustice, pain, and deaths on the Earth? All these and similar questions are damned. They come from the depth of the human soul; they torture us and provide no final answers. Their primary sense is to be damned, and they usually arise when previous answers confront the current state of reality, or, in other words, when previous solutions become invalid. These questions arise at times like these.

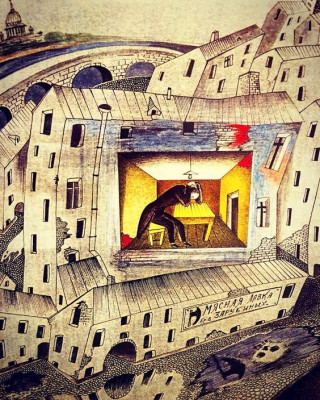

Criminology, at first sight, is far away from the area of damned questions. Despite its metaphysical origin, criminology started rather as a rational economic project, elaborated abstract principles of free choice and utilitarian vision of social contract. Under C. Beccaria approach (1764), crime is understood as a selfish and poorly calculated enterprise, which could be effectively tackled by the better calculated and socially responsible punitive policy. However, this vision was strongly challenged by F. Dostoevsky, whose 200th anniversary will be celebrated this year. In his book, which title "Crime and Punishment" (1866) was copied from the classic Beccaria's work, the perpetrator's existential appeal for absolute freedom and unlimited willpower opposes the rational choice in wrongdoing, while the transgressor's confession and religious salvation substitute the legally grounded proportional punishment. In the 19th century, which was the age of science and progress, criminologists entirely neglected this existential approach. However, in the next politically turbulent and tragic 20th century, these and similar ideas became more visible in criminological texts. Their traces can be easily recognized in D. Matza's appeal (1969) to understand the inner drives and motives in "becoming deviant", or in N. Cristie's sad irony on seeking the "limits to pain" in criminal justice (1981) and prophetic vision of current penal policy as driving "toward Gulag, western style" (2000).

As an intellectual product of the 18–19th centuries, criminology had inherited not only its metaphysical "damned questions", but also its naïve belief that advanced scientific knowledge could help create more just and less conflicted societies. Today we probably are more experienced and knowledgeable about social, economic, political, and biological crime roots than our predecessors. However, precisely because of this very knowledge, we are also more critical towards popular enthusiasm to create a crimeless society. Damned, unanswered questions still lead us, and the pandemic makes these questions even more acute. Crime is not a mere social fact; crime is also a social construct expressing the dynamic of social conflicts and consensuses in society. On the one hand, we have a good chance and duty to discover how crime patterns, human behaviours and criminal justice operation change in pandemics and after the pandemic situation. On the other hand, we need to turn our attention to the changing landscape of social control, where new players like transnational and national public health institutions, IT and Biotech corporations are going to change drastically our previous understanding of what should be acceptable and unacceptable in a new post-pandemic world.

How criminologists could react to these challenges in the time of "weak states" and "inefficient government"? Will criminology play the role of "boring" intellectual tool in the hands of invisible power? Or should it occupy an uncompromising position against attempts to seek and implement the "new normalization" of society? My predecessor Prof. Lesley McAra in her presidential address (2020), devoted to the new challenges and role of criminology and ESC in the time of the pandemic, formulated her vision in the following passage: "I believe we need to re-engage with a number of normative questions: what are the conditions of a just social order; what promotes social solidarity; what are the structural conditions which support human flourishing; how can human rights discourse come to infuse and transform institutional cultural practices?" One could agree or disagree with this agenda, but I hope this proposal will be a matter of further academic discussions and practical policy-making initiatives. However, for the time being, I would like to stress a more general issue – old "damned questions" today require new criminological insights and answers.

Dear Colleagues, despite all the troubles and obstacles our society and its members' academic activity have never been stopped generating new projects, publications, educational programs and expertise. Recently, in my alma mater, Vilnius University, we had a remarkable event – 48 graduates have received their Bachelor diplomas in Criminology – the first Bachelor Program in Criminology nationwide. Another small 'evidence-based' proof that our criminological communities are alive and thriving. On this positive note, I would like to wish all of us good health, optimistic thoughts, and express my hope to meet you soon at the online 21st Annual Conference of the European Society of Criminology!

Artwork: Raskolnikov in St Petersburg © The Russian Arts Theatre and Studio