Is Spain a socially exclusionary country for criminal offenders?

Is Spain a socially exclusionary country for criminal offenders?

Is social exclusion a criterion for comparative criminal policy?

Social exclusion as an effect of criminal policy has not been questioned in academic debates, although they mostly focus on punitiveness as an essential feature of contemporary criminal policy. However, the use of this guiding criterion in the study of comparative criminal policy shows a set of theoretical and methodological flaws (Díez-Ripollés, 2011 and 2013).

On the one hand, punitiveness, or its opposite, punitive moderation, is rather limited from a theoretical point of view, as it only ensures that any crime control system -irrespective of the criminal policy model applied or the objectives pursued-, does not reach levels of harshness that are considered unacceptable. However, it does not offer a social intervention strategy that, understood as a public policy, develops specific and measurable objectives aimed at preventing crime within, in any case, socially assumed parameters. In this sense, its shortcomings are parallel to those of approaches strictly based on rule of law and due process values, which are essential to safeguard civil liberties and fundamental rights, but do not attempt to identify and structure a criminal policy alternative that, while compatible with those values, proposes a certain strategy to combat crime (Lahti 2000; Díez-Ripollés 2004).

From a methodological perspective, the goal of punitive moderation uses excessively limited indicators. In fact, it predominantly focuses on one, the incarceration rate per 100,000 inhabitants. This indicator certainly has many virtues: It is easily accessible from various reliable sources; since it has been recorded for a long time, it allows to have data series covering extended time periods; it focuses on the harshest sanction that a criminal system can impose, except for the death penalty; and it is usually a sanction which reflects well the outcome of the whole criminal policy of the respective national system (Cavadino and Dignan 2006; Tonry 2007). However, the criminological and criminal policy doctrine has repeatedly revealed its shortcomings: Above all, for unduly focusing the evaluation of a criminal justice system’s severity on the use of imprisonment, marginalizing other indicators with a strong capacity to express the intensity of the punitive reaction, such as the number of criminal proceedings and those resulting in a conviction, the duration of penalties in general, the intensity and frequency of use of penalties other than imprisonment or the accumulation of sentences, among others (Hinds 2005; Tonry 2007; Nelken 2005 and 2010; Tamarit Sumalla 2007; Lappi-Seppälä 2007 and 2008; Roché 2007; Newburn 2007; Larrauri Pijoan 2009).

For those reasons Díez-Ripollés (2011 and 2013) has proposed a new model, which aims to be an alternative to the current strong trend of comparing national crime control systems according to their higher or lower level of punitiveness. Paying specific attention to four significant groups, because they are in direct contact with crime intervention bodies, namely, suspects, defendants, offenders and exoffenders, the theoretical model of Díez-Ripollés departs from the criterion of punitiveness versus punitive moderation and chooses instead that of social exclusion versus social inclusion. Both concepts of this criterion reflect two contrasting approaches to the criminal policy goal of preventing crime. The socially exclusionary approach is essentially aimed at achieving the incapacitation of the designated groups, which implies ensuring that suspects, defendants, offenders and ex-offenders find themselves -after their contact with penal institutions-, in individual and social conditions where it will be more difficult for them to break the law or to avoid being discovered. Conversely, a socially inclusionary approach seeks, above all, the social reintegration of those groups, so that suspects, defendants, offenders and ex-offenders find themselves -after their contact with penal institutions-, in equal or better individual and social conditions to voluntarily lead a law-abiding life. Assumed hypotheses are that a mostly social inclusive system is one of the most effective strategies for crime prevention in the mid and long term and, on the contrary, a mostly social exclusionary system will foster greater levels of crime in the mid and long term.

As a result, the different national crime control systems would have to be evaluated according to the extent to which their penal intervention models adhere to one of those two approaches. The instrument presented below intends, more modestly, to measure the greater or lesser distance various crime control systems show on social exclusion.

How to measure the social exclusion of a national penal system?

The theoretical model of Díez-Ripollés (2011, 2013) identifies nine major areas of penal intervention especially adequate to reveal relevant exclusionary effects that, as a whole, offer a comprehensive picture of the corresponding criminal justice system. The nine areas or pools are: Control of public spaces (gated communities, video surveillance, restriction of access to public spaces), legal safeguards (undermining of due process safeguards, hindering or restriction of legal remedies), sentencing and sanction systems (judicial discretion, aggravated provisions for recidivists, extensive use of prison, community sanctions, electronic monitoring), harshest penalties (death penalty, life imprisonment, long-term prison sentences), prison rules (living conditions in prison, respect for prisoners' rights, release on parole), preventive intervention (pre-trial detention, indefinite preventive detention), legal and social status of offenders and ex- offenders (disenfranchisement, deprivation of further civil rights, accessibility to social resources), police and criminal records (extension and accessibility of records, community notifications), and youth criminal justice (age thresholds, treatment differentiated from adults) (Díez-Ripollés 2011 and 2013).

Other possible pools were discarded for different reasons. Thus, for example, criminal policy on drugs was discarded because it was considered to have little discriminatory capacity when making international comparisons of national criminal systems. Procedural rules and practices for prosecuting crimes were also discarded as being too broad and multiform, as well as posing difficulties when comparing systems that are governed by the principle of opportunity versus those that are governed by the principle of legality.

Once the areas that provide a complete picture of the criminal justice system in different countries had been identified, the challenge was how to measure this independent variable in order to obtain valid results from a significant number of countries that could be compared with each other.

The Malaga Institute of Criminology team's proposal for measuring social exclusion to compare different national penal systems is the RIMES instrument.

What is RIMES instrument?

Based on Díez-Ripollés' conceptual model, it was considered appropriate to design a questionnaire consisting of a set of indicators to measure the extent to which the different national penal systems produce socially exclusionary effects on the groups most likely to encounter criminal law. This questionnaire contains indicators consisting of punitive norms and practices related to nine relevant areas of penal intervention identified in the theoretical model. A punitive rule is understood as a legal standard that can be included in the criminal law system, establishing certain consequences for certain behaviours or situations related to crime control. A punitive practice means the way in which different social agencies react to behaviours or situations related to crime control, in accordance or not with the provisions laid down by the law.

The RIMES instrument can make this measurement since it has been subjected to a rigorous process of validation by inter-judge agreement, involving nearly 100 international experts from 18 Western countries. Thus, these prominent and numerous experts agreed that the punitive rules and practices selected as indicators significantly produce social exclusion of suspects/defendants, offenders, and ex-offenders (Díez-Ripollés and García-España 2019; Díez-Ripollés 2021; García-España 2021). No attempt whatever has been made to empirically verify through fieldwork whether those punitive rules or practices generate social exclusion. Such verification has been replaced by its validation through a broad consensus among experts.

The RIMES instrument comprises 39 indicators. All those 39 indicators that compose the RIMES instrument have the same characteristics: they involve real punitive rules and practices, namely, they are effectively applied or seriously considered in Western developed countries; they have a strong capacity to measure significant social exclusion effects on the groups under study; they comprehensively reflect, as a whole, the reality of the criminal policy model of their respective countries in terms of their socially exclusionary effects on the targeted groups; and they have discriminatory power, that is, they can show relevant variations in the different crime control systems of the developed Western world.

The RIMES instrument applied in Spain is set out in Table 1 below, with the indicators/items grouped by pools and distinguishing between rules and practices.

Table 1. The RIMES instrument by thematic pools

|

Pools |

Rules |

Practices |

|

1. Control of public spaces |

1. Any person may be arrested for repeated street begging |

11. Discriminatory street police interventions (stop and search, arrests, frisks/body searches…) targeting specific groups occur regularly |

|

2. An individual may be arrested for loitering |

||

|

3. At its discretion, the police may enforce restrictions on specific individuals to access some public spaces (parks, squares, streets…) |

||

|

2. Legal safeguards |

21. The criminal justice system lacks indigent defense services |

25. A significant number of mentally ill inmates serve their sentences in regular correctional facilities |

|

22. Payment of court fees is legally required from the defendant in order to get access to appellate review |

||

|

24. The regular term for police detention established by the law exceeds 5 days |

||

|

3. Sentencing and sanction systems |

33. In the case of prison sentences, neither probation as an alternative to sentencing nor suspended sentences are envisaged in the law |

37. The incarceration rate is higher than 120 inmates per 100,000 inhabitants |

|

35. The law lacks provisions for penalties other than prison (community service, fines, house arrest…) in case of less serious felonies |

38. At least three quarters of the inmates are serving their sentences in closed prisons |

|

|

36. Default imprisonment is the sole alternative to non-payment of a fine |

||

|

4. Harshest penalties |

42. Death penalty is legally available |

50. Those sentenced to life imprisonment regularly serve more than 25 years |

|

43. Life imprisonment without release is legally available |

52. Life imprisonment is imposed on ethnical or racial minorities, or on people in poverty in over 80% of cases. |

|

|

5. Prison rules |

55. The system lacks a specific prison regime for young adults |

68. Family and intimate visits take place at intervals of over one month |

|

62. The law lacks statutory provisions regulating inmates’ legal assistance for penitentiary matters |

||

|

64. The law requires payment of fees by the inmate before claiming judicial review of penitentiary decisions |

||

|

6. Preventive intervention |

74. Preventive detention may last for an unlimited period of time |

81. The average length of preventive detention exceeds 5 years |

|

79. The maximum statutory term for pretrial detention exceeds 3 years |

82. Over 30% of the prison population is in pre-trial detention |

|

|

7. Legal and social status of offenders and ex-offenders

|

86. Those sentenced to up 3 years of imprisonment for any criminal offence may be deprived of the right to vote for over 4 years after serving their sentences |

|

|

88. Legally resident foreigners may be deported if they receive a custodial sentence up to one year or a non-custodial sentence |

||

|

91. Those sentenced to up to 3 years of imprisonment are prohibited from doing certain jobs not connected with their offences or with law enforcement for a period of more than 5 years after their sentence has been completed |

||

|

92. Those sentenced to up to 3 years of imprisonment for any criminal offence are not eligible for public housing for a certain period after having served their sentences |

||

|

93. Nationals sentenced to imprisonment for any criminal offence are not eligible for welfare benefits for a certain period after having served their sentences |

||

|

8. Police and criminal records |

99. Private employers, who are not related to private security companies or to those working with children or vulnerable adults are entitled to request information about criminal records to potential employees. |

107. The media regularly disclose the full names, current addresses or pictures of ex-felons |

|

100. Anyone may request information about other people’s criminal records without needing to argue grounds established by law |

||

|

101. The criminal records of any citizen are legally accessible through internet |

||

|

9. Youth criminal justice |

113. Youth justice applies to children who are 12 years old or younger |

121. Custodial sanction is one of the three most common sanctions applied to minors |

|

117. Youth justice provides custodial sanctions of over 10 years |

126. Alien minors are deported because of an offence |

|

|

120. Minors’ criminal records keep legal effects after reaching the age of majority |

What are the results of the implementation of RIMES in Spain?

As a pilot project, this tool has been applied in Spain. Implementation of the RIMES instrument in Spain was settled with 31 items expressing social exclusion that were answered in the negative, against 8 items that were answered in the affirmative. However, during the application of the RIMES instrument in other six jurisdictions -Germany, Italy, Poland, England & Wales, California and New York-, the RIMES team decided to replace item 52 by item 46 in pool 4. Adopting this modification, the results obtained in Spain were 30 items answered in the negative, against 9 items that were answered in the affirmative Table 2 shows those last 9 rules and practices according to their pool of origin.

Table 2. Items answered in the affirmative in Spain distributed by pools.

|

Pools |

Items |

Rule or practice |

|

1. Control of public spaces |

11. Discriminatory street police interventions (stop and search, arrests, frisks/body searches...) targeting specific groups occur regularly. |

Practice |

|

2. Legal safeguards |

None |

|

|

3. Sentencing and sanction systems

|

37. The incarceration rate is higher than 120 inmates per 100,000 inhabitants. |

Practice |

|

38. At least three quarters of the inmates are serving their sentences in closed prisons. |

Practice |

|

|

4. Harshest penalties |

46. A minimum of 20 years served is required before claiming release from life imprisonment |

Rule |

|

5. Prison rules |

None |

|

|

6. Preventive intervention |

79. The maximum statutory term for pretrial detention exceeds 3 years. |

Rule |

|

7. Legal and social status of offenders and ex-offenders

|

88. Aliens with residence permits may be deported if sentenced for any criminal offence either up to 1 year of imprisonment or to any other non-custodial sentence. |

Rule |

|

8. Police and criminal records |

99. Private employers, who are not related to private security companies or to those working with children or vulnerable adults are entitled to request information about criminal records to potential employees. |

Rule |

|

107. The media regularly disclose the full names, current addresses, or pictures of exfelons. |

Practice |

|

|

9. Youth criminal justice |

121. Custodial sentences are one of three types of sanctions which are most frequently applied to minors. |

Practice |

Most of the items that were answered in Spain in the affirmative are practices, 5, compared to only 4 rules. The four rules answered in the affirmative are distributed among the pools concerning “harshest penalties” (pool 4), "preventive intervention" (pool 6), "legal and social status of offenders and ex-offenders" (pool 7) and "police and criminal records" (pool 8). For their part, the practices answered in the affirmative belong to the pools concerning “control of public spaces”, “sentencing and sanction systems”, “police and criminal records”, and “youth criminal justice”. The percentage of those practices in the instrument’s total practices (n = 12) is 42%, while the 4 rules answered in the affirmative represent 10,25% of the total rules that make up the instrument, which are 28. Considering the number of rules and practices answered in the affirmative -both in absolute and in relative terms-, we can say that in Spain the socially exclusionary effects are noticeable not so much in the rules as in a certain way of applying some of them.

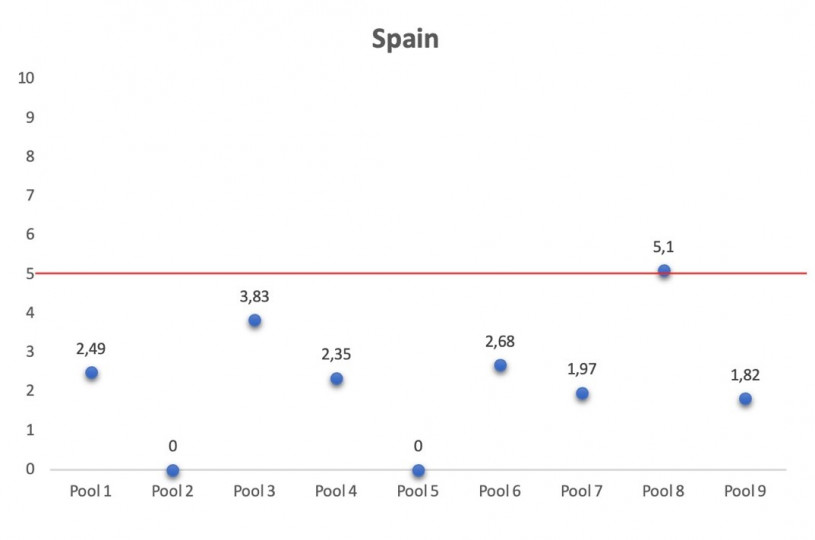

Taking into consideration the distribution in pools (see scoring by pools in Figure 1), in Spain there is at least one indicator expressing social exclusion in seven of the nine pools. Pools 2 (legal safeguards) and 5 (prison regime) have all their items answered in the negative, namely, there is no item expressing social exclusion in Spain. However, it is pool 8 on “police and criminal records” that generates most social exclusion, with a score of 5.10, followed by "sentencing and sanction systems" (pool 3) with 3.83. In this pool, moreover, only practices generate exclusion, which is a difference compared to the rest of the pools.

Figure 1. Social exclusion scores according to pools

The Spanish prison policy has been internationally characterized by its enlightenment. This is somehow revealed by the fact that no indicator of the pool regarding "prison rules" (pool 5) has been answered in the affirmative. As regards this pool, the items pertaining to the death penalty and the possibility of reviewing life imprisonment show a Spanish criminal policy that is far from the parameters of social exclusion, although the indicator related to average duration of reviewable life imprisonment cannot be answered due to recent incorporation of this penalty into the Spanish Penal Code,

One of the results from the implementation of the RIMES instrument in Spain is that it corroborates the need to address the comparison of national criminal policies with an alternative model to punitiveness. It should be noted that the pool where more items have been answered in the affirmative has been the one referring to the "sentencing and sanctions system". In particular, the incarceration rate in Spain exceeds 120 per 100,000 inhabitants and at least three-quarters of the inmates are serving time in closed prisons. If the international comparison had been limited to the incarceration rate or to this and some other similar indicator, the Spanish criminal policy would have been labeled as rigorist. However, by using a more complex comparative model, which considers a greater number of criminal intervention measures -as is the case with the RIMES instrument-, things look different. The Spanish criminal policy assessed as a whole, and regardless of subsequent comparisons with other countries, does not seem to be particularly exclusionary. This result calls into question some proposals that consider the incarceration rate to be a sufficiently comprehensive indicator for the purpose of characterizing national criminal policies (Lappi- Seppälä 2008; Webster and Doob 2007).

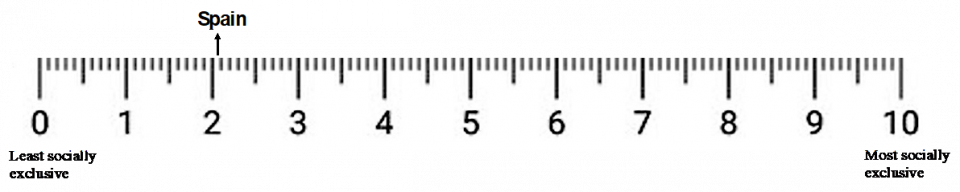

A substantial majority of criminal policy indicators expressing social exclusion (31 indicators) do not occur in the Spanish case. We can offer -as a hypothesis- that an affirmative response in 8 of the 39 items (20% of affirmative responses) may show that the Spanish penal system does not generate much social exclusion. We have based ourselves on the position it holds in the continuum made up by the extremes of greater or lesser social exclusion, where Spain is located closest to the pole of less social exclusion (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Spain's position in the continuum, from least to most social exclusion

Without considering results obtained from the application of the instrument in other countries, the position got by Spain seems to prove at a first glance that RIMES is sufficiently discriminating to the extent that it leaves room on both sides to place criminal policy systems from other countries that could generate more or less social exclusion than the Spanish one. In other words, and judging by the case in Spain, the instrument does not tend to take countries to one of the two extremes.

Are you interested in the results of exclusion generated by other countries?

Once this implementation has been explored in Spain, RIMES makes sense as an instrument for international comparison. That is why the RIMES team is currently engaged in applying the instrument at an international level. We have already applied the instrument to the criminal systems of four European countries (Poland, United Kingdom, Germany and Italy) and two states of the USA (California and New York), checking whether the 39 items that composed the instrument concur. Two of the team researchers solved all 39 items at each of the six chosen locations. For guiding and helping us to obtain the information we need, we have contacted with at least one expert in this field of each country, usually chosen from the country experts who previously collaborated in the validation of the instrument. In the end, another expert from each country under study reviewed the results obtained, by means of a report in which he/she assessed whether the research team had worked properly on each of the tool’s items, thus confirming the reliability of responses. With all this, we finally have the results of the application of the RIMES instrument in 7 jurisdictions (including Spain) which we hope to be able to show and discuss at the next Eurocrim 2022 to be held in September in Malaga (Spain).

Literature.

Cavadino M, Dignan J (2006) Penal Systems. London: Sage Publications.

Díez-Ripollés JL (2004) El nuevo modelo penal de la seguridad ciudadana, Revista electrónica de ciencia penal y criminología. 06-03: 1-34.

Díez Ripollés JL (2011) La dimensión inclusión / exclusión social como guía de la política criminal comparada. Revista electrónica de ciencia penal y criminología. 13-12: 1-36.

Díez-Ripollés JL (2013) Social Inclusion and Comparative Criminal Justice Policy. Journal of Scandinavian Studies in Criminology and Crime Prevention. 1: 62-78.

Díez Ripollés JL, García España, E (2019) RIMES: An Instrument to Compare National Criminal Justice Policies from the Social Exclusion Dimension, International E-Journal of Criminal Sciences, 1, 13: 1-27

Díez Ripollés JL (2021) La utilidad político-criminal del instrumento RIMES, in Cerezo Domínguez, AI coord. Política criminal y exclusión social, Valencia: Tirant lo Blanch

García España E (2021) Instrumento RIMES: Una propuesta para el análisis comparado de la política criminal, in Cerezo Domínguez, AI coord. Política criminal y exclusión social, Valencia: Tirant lo Blanch

Hinds L (2005). Crime Control in Western Countries In: Pratt J, Brown D, Brown M, Hallsworth S, Morrison W The New Punitiveness, Cullompton: Willan Publishing.

Lahti R (2000) Towards a Rational and Humane Criminal Policy. Journal of Scandinavian Studies in Criminology and Crime Prevention. 1: 141-155.

Lappi-Seppälä T (2007) Penal Policy in Scandinavia, in Tonry M ed. Crime, Punishment and Politics in Comparative Perspective, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lappi-Seppälä T (2008) Trust, Welfare, and Political Culture, in Tonry M ed. Crime and Justice. n. 37. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Larrauri E (2009) La economía política del castigo, Revista electrónica de ciencia penal y criminología. 11-06: 1-22

Nelken D (2005) When is a Society Non-punitive? The Italian Case, in Pratt J, Brown D, Brown M, Hallsworth S, Morrison W The New Punitiveness, Cullompton: Willan Publishing.

Newburn, T (2007). ‘Tough on Crime’: Penal Policy in England and Wales, in Tonry M ed. Crime, Punishment and Politics in Comparative Perspective, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Nelken D (2010) Comparative Criminal Justice, Los Ángeles: Sage Publications.

Roché S (2007) Criminal Justice Policy in France, in Tonry M ed. Crime, Punishment and Politics in Comparative Perspective. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Tamarit JM (2007) Sistema de sanciones y política criminal, Revista electrónica de ciencia penal y criminología. 09-06: 1-40.

Tonry M (2007) Determinants of Penal Policies, in Tonry M ed. Crime, Punishment and Politics in Comparative Perspective, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Webster CM, Doob A (2007) Punitive Trends and Stable Imprisonment Rates in Canada, in Tonry M ed. Crime, Punishment and Politics in Comparative Perspective, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Authors’ affiliation: Elisa García-España is Professor of Criminal Law and Criminology at the University of Málaga. elisa@uma.es Professor José Luis Díez-Ripollés is Professor of Criminal Law at the University of Málaga. ripolles@uma.es