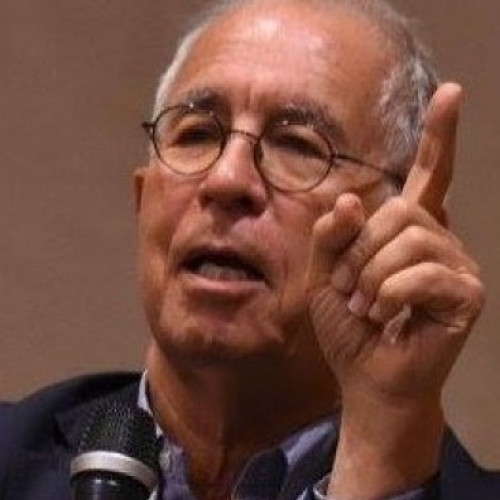

25 years of the ESC - the memories of Ernesto U. Savona (ESC president 2003-2004)

In 2003, when I was elected President of the ESC, the driving idea was the opening of the European Union to Eastern European countries. Some of us were enthusiastic that cultural and geopolitical barriers were falling, paving the way for greater exchange, collaboration, and friendship within Europe and beyond. Over the past 25 years, we have upheld these values within the ESC. The result is a European criminology without borders—young in spirit and in age, open to new ideas, yet proud of its traditions.

Today, as we celebrate the 25th anniversary, the world has changed dramatically. Issues we never believed could resurface—such as genocide and human rights violations—have become part of daily narratives. The debate now revolves around increasing the production and trade of firearms, both small and large, despite our belief over the past 25 years that nations should strive to reduce arms, remove them from the hands of criminals, and restrict their use to law enforcement. The American experience demonstrates that easy access to firearms facilitates violent crime. These developments bring us back to the aftermath of World War II, when criminology, particularly in the United States, was taking its first steps.

What is the impact of these contemporary challenges on the development of criminology?

First, we must defend the progress we have achieved so far. This includes the growth of multilateral institutions such as the United Nations, the International Criminal Court, and international police organisations, which emerged after World War II and the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. Their contributions to analysing and strengthening international cooperation in combating cross-border crime, investigating war crimes, punishing dictators, and capturing fugitives have been crucial to the advancement of criminology.

Second, we must integrate more technology into our research efforts, leveraging the advantages of Artificial Intelligence to understand and predict crime while respecting privacy and avoiding discrimination.

Third, we should focus more on the policy implications of our research. Policy priorities could inform research priorities, and vice versa. For example, policies aimed at freezing and confiscating the proceeds of crime are theoretically effective in combating organised crime but often fail in practice to deter criminal behaviour. This gap highlights the need to improve international judicial and police cooperation, which remains a challenge despite the conventions established to strengthen this framework.

Fourth, we must consider the future. How will the current geopolitical turmoil - marked by insecurity, arrogance, violence and vulgarity - impact crime? Amid these changes, with uncertain short- and long-term outcomes, it is difficult to outline a clear scenario. It is possible that stricter immigration policies in the Western world may reduce illegal migration. However, these policies may be offset by push-and-pull factors driven by rising social and economic inequalities in developing regions such as South America, Africa, and the Middle East. This could increase demand for illegal migration, expanding the operations of criminal organisations involved in migrant smuggling and trafficking. Once migrants arrive, their illegal status and marginalisation may create a propensity for crime.

In the realm of organised crime, these dynamics are likely to further complicate efforts to uphold security and justice. But what of violent and property crime? We anticipate that rising inequalities, coupled with increased defence spending at the expense of social welfare, will exacerbate criminal activity. Such shifts, which prioritise destruction over construction, are likely to fuel both violent and property crime. This is to say nothing of cybercrime, which continues to grow unchecked, aided by the impunity of perpetrators and the limited awareness of victims.

In conclusion, the world is undergoing profound change, and its trajectory remains uncertain. The present and future generations of criminologists must rise to the challenge of interpreting these shifts. This will require a steadfast commitment to defending core values, refining methodologies, and addressing the priorities outlined by contemporary crime-fighting policies.