Blog

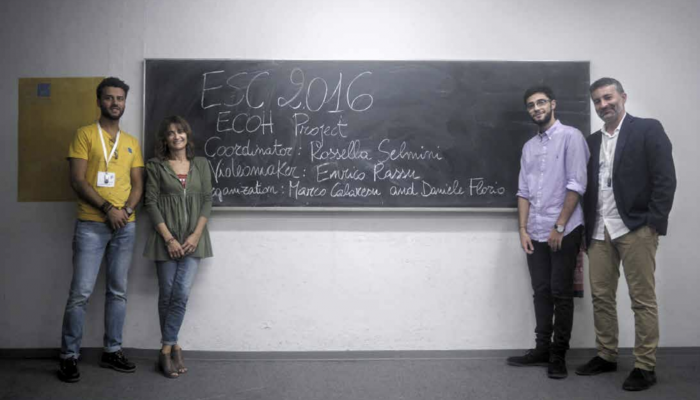

25 years of the ESC - the memories of Rossella Selmini (ESC President 2016-2017)

The memories of Rosella Selmini (ESC President 2016-2017)

25 years of the ESC - the memories of Tom Vander Beken (ESC President 2018-2019)

The memories of Tom Vander Beken

25 years of the ESC - the memories of Lesley McAra (ESC President 2019-2020)

Reflections on the ESC at 25 from a Past President

2025 At-large Board member: candidate Alina Deana Machande

Candidates to the ESC board – 2025

2025 Election of ESC President: Letizia Paoli

2025 Candidates to the ESC Board: candidate profile

25 years of the ESC - the memories of Sonja Snacken (ESC president 2004-2005)

Sonja Snacken, ESC president 2004-2005

25 years of the ESC - the memories of Vesna Nikolic-Ristanovic (ESC president 2012-2013)

Vesna Nikolic-Ristanovic, ESC president 2012-2013

25 years of the ESC - the memories of Martin Killias (ESC president 2000-2001)

The memories of Martin Killias

New ECOH interview: Hans-Jörg Albrecht

Hans-Jörg Albrecht interviewed by Anna-Maria Getoš Kalac (2024)

25 years of the ESC - the memories of Elena Larrauri (ESC president 2008-2009)

"a privilege to have been able to know, come close and share conversations"

25 years of the ESC - the memories of Ernesto U. Savona (ESC president 2003-2004)

25 Years of ESC: Changing World, Evolving Criminology

25 years of the ESC - the memories of Gorazd Meško (ESC president 2017-2018)

"Europe is a very diverse place, and the same goes for the ESC and its members"

25th anniversary of the European Society of Criminology: Call for Memories

Call for Memories

New ECOH Interview: Loraine Gelsthorpe

Loraine Gelsthorpe interviewed by Michele Burman (2023)

New ECOH interview: Josep M Tamarit- Sumalla

Josep M Tamarit- Sumalla interviewed by Antonia Linde (2023)

ECOH - new interviews!

ECOH will soon be releasing the interviews conducted during EUROCRIM2023.

Tom Vander Beken interviewed or ECOH

Tom Vander Beken interviewed in Malaga, Spain, September 2022, at the 22nd Annual Conference of the European Society of Criminology (ESC).

Catrien Bijleveld for ECOH

The former ESC president Catrien Bijleveld interviewed for the ESC oral history project

Open Call for Associate Editors for the European Journal of Criminology

In recent years the European Journal of Criminology has seen a steep rise in submissions, which cover a wide range of topics relating to crime and criminal justice. To support an effective and efficient peer review process, Associate Editors (AEs) have become a key asset of our Editorial Team. We ar...